Iconic recipes have to come from somewhere. Welcome to First Draft Foods, a week where we delve into the legends and controversies behind the world’s favorite dishes. Previously, we learned about the origins of red velvet cake and chowder.

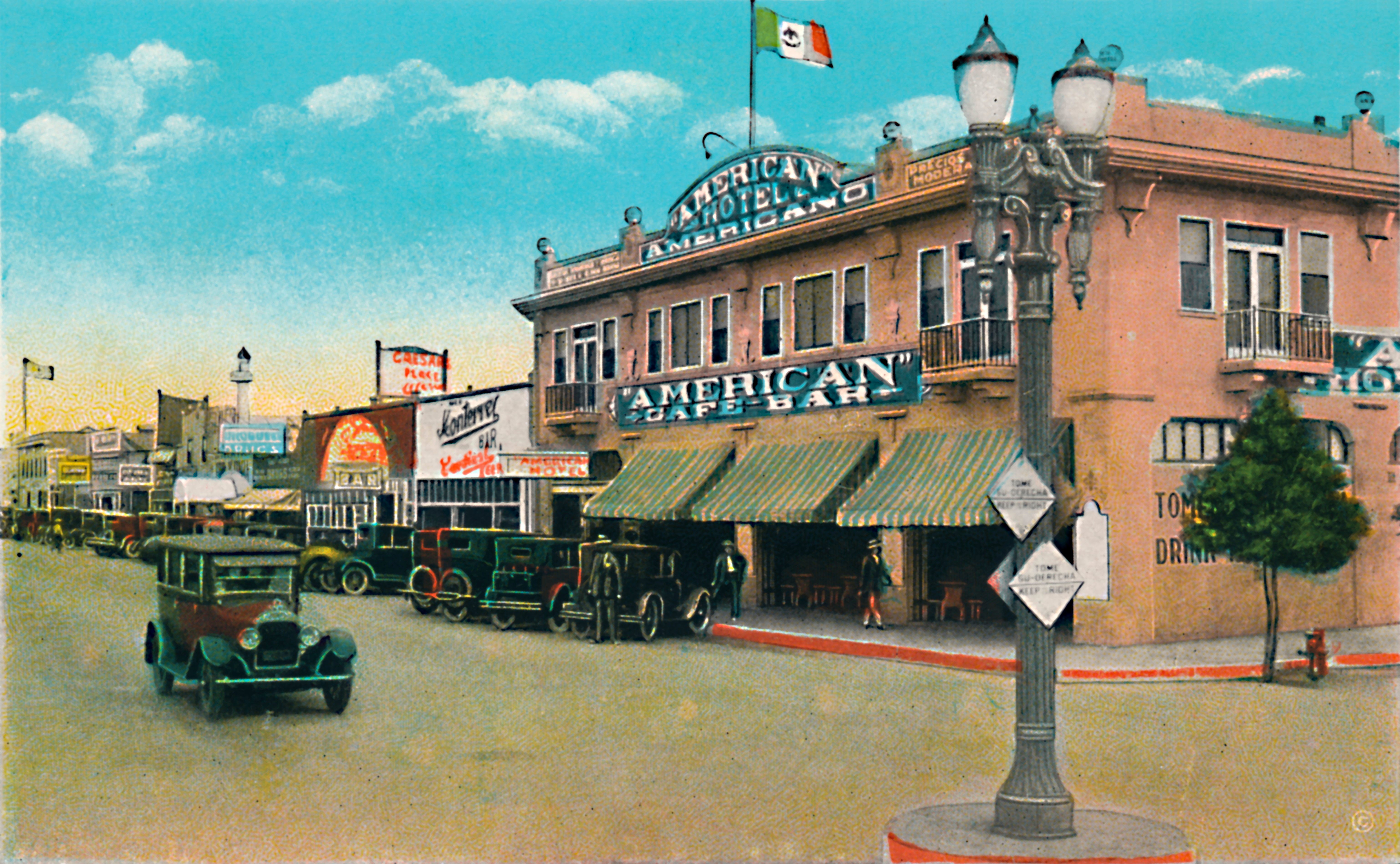

This much we know to be true: In the 1920s, Tijuana was the place to be. Prohibition was the law of the land north of the US-Mexico border, but along Avenida Revolución, there was smoking, drinking, dancing, gambling, and assorted other vices on offer.

The avenue boasted “the world’s longest bar”—215 feet, staffed by ten bartenders and 30 waitresses—and a bordello topped with a red windmill, the Molino Rojo. Scores of clubs and restaurants beckoned to Hollywood’s biggest stars. Lon Chaney and John Barrymore dined at the San Francisco, while the boxer Jack Johnson held court at the Black-only Newport. Clark Gable, Rita Hayworth, W.C. Fields were all regulars at the various restaurants owned by one or the other of the Cardini brothers; Alex and Caesar were the best-known hosts of this never-ending, blocks-long party.

And amidst all this indulgence and showmanship, there was a salad.

Perhaps only this moment of determined decadence could have created the Caesar salad. In the 1920s, lettuce-based salads were trendy, but what was on offer in Tijuana was something different than the iceberg and butter lettuces available in the States.

This long crisp and sweet leaf was exotic; it was preferred by Europeans who called it cos and it was hard to find outside of kitchen gardens in the United States. On Avenida Revolución, cos—now better known as romaine—was the star of a grand show, tossed table side with a flurry of imported ingredients until each leaf dripped with rich, creamy sauce. It was a messy feast, meant to be eaten with abandon, right at that moment, and always with one’s fingers.

This unexpected salad became so beloved that it did not disappear with the Tijuana crowds when Prohibition was lifted in the United States and the Mexican government banned gambling. As the city where it was created withered, the salad found its way onto menus in Los Angeles and then New York. Bottled versions of the dressing appeared on supermarket shelves, countless recipes filled newspaper food sections, and commercial production of romaine lettuce boomed.

All that is true. What we don’t know for sure—what we will likely never know —is the true origin of this world-famous salad. The questions of who deserves credit for it, what it should properly be called, and exactly how it was first made have divided both the Cardini family and North America’s leading food writers for generations.

As Rosa Cardini—Caesar Cardini’s daughter—told the story, the Caesar salad was created on July 4, 1924, five years before she was born, at Caesar’s Place on Callejón del Travieso in Tijuana. High demand that hot Friday night meant the kitchen was running low on some ingredients, so Caesar took stock of his supplies, rolled up his sleeves and began to experiment.

He started with crisp, cool romaine lettuce. Then he coddled an egg, cooking it for just one minute to thicken the yolk—“it holds the ingredients together and makes them coat the leaves,” Rosa often explained. He whisked the egg with freshly ground pepper, lemon juice, salt, Worcestershire sauce, garlic-infused olive oil, and Parmigiano Reggiano. Finally, he tossed the creamy dressing with the romaine leaves and topped the dish with croutons. The final ingredient was some theater: “He came right to the table and tossed the ingredients in the right order,” Rosa would say.

And she would say it often. Her father wanted the world to know he was the salad’s namesake. Caesar bemoaned all the copycat Caesar salads—and all those who would claim the title of inventor, a group that included his brother, his brother’s former business partner, and, inexplicably, a movie producer/suspected mobster named Pat DiCicco. “I originated it 28 years ago in Tijuana, Mexico, and these others, they just aren’t the same,” he told a United Press reporter in 1952.

Caesar was by then far removed from the heady days of Avenida Revolución; he was a grocer in Hollywood, making his salad dressing in a tiny kitchen behind his store. When he passed away a few years later at the age of 60, Rosa took on the task of protecting her father’s legacy.

Rosa’s story never changed, but the recipe she shared shifted in small ways over the years. Sometimes, it included vinegar—a teaspoon of fruit or wine vinegar (and in one 1969 recipe, specifically red wine tarragon vinegar)—and sometimes it didn’t. After Rosa gave Julia Child the recipe in the 1970s sans vinegar, that became the “authentic” version for most people. Child also resurrected the over-the-top presentation of the dish that usually went unmentioned in Rosa’s instructions for the home cook, including the directive that the lettuce leaves be served whole and eaten as finger food.

Child recalled a trip to Tijuana with her parents in 1925 or 1926 when she was a young teenager and reminisced about a memorable lunch at Caesar’s restaurant. “Caesar himself rolled the big cart up to the table [and] tossed the romaine in a great wooden bowl,” she wrote. “It was a sensation of a salad … How could a mere salad cause such emotion?” To recapture that experience, Child instructed her readers to “use large rather slow and dramatic gestures for everything you do, as though you were Caesar himself.” Each ingredient was added one at a time, punctuated with rolling tosses, the salad leaves tumbling “like a large wave breaking toward you.” Child recommended eight of these tosses; Rosa, however, disagreed with the famed chef on this point. Her instructions were clear: “Toss no more than seven times.”

Rosa, who passed away in 2003 after almost 50 years spent defending what she called “a work of genius,” harbored deep disdain for those who adulterated her father’s Caesar salad with raw eggs, imitation cheeses—or worse, blue cheese—tomatoes, cucumbers, chicken and even fettuccine. But by far her biggest nemesis was the cook who would dare add anchovies to the dish: “There were never any anchovies.”

Alex Cardini—Rosa’s uncle—told a very different creation story for Caesar salad, one that most definitely included anchovies.

“I am the originator of the Caesar salad and the original recipe is my personal one!” Alex boasted to a Chicago Tribune reporter in 1967. In the early 1950s, about the same time Caesar began agitating for recognition, Alex had emerged as a claimant to the title of the “Caesar salad man,” as one newspaper called him. In his earliest known telling of the tale in 1954, Alex created the salad at Paul & Alex’s, which opened in the late 1920s, as the “aviator salad” a tribute to the airmen who were regulars at the restaurant, and a nod to his own experience as a pilot in the Italian armed services during World War I. “But Caesar later made it famous,” Alex laughed, at the time. “He gave it the most publicity.”

The competition was much more fierce and less funny by the 1960s as demand for bottled Caesar dressing increased. Both sides of the family had their own versions to sell. While Caesar’s version of the story had the support of America’s top expert on French cuisine, Alex had its top expert on Mexican cuisine in his corner: Diana Kennedy. In 1974, Kennedy dined with Alex, who had become a prominent restaurateur in Mexico City. She recorded the recipe for the “original ensalada Alex-César Cardini,” as she called it. That version called for lime juice rather than lemon (over the years, Alex would use both, but he said lime was the classic), no vinegar (which Alex claimed was an invention that came with the advent of bottled dressings), and six anchovy fillets for two servings, to be mashed together with garlic and spread on to the croutons.

By the time of his death a few months after his dinner with Kennedy, it was already clear that Alex would lose the titles of “original” and “authentic” to Caesar. Rosa’s one-woman public relations campaign was too formidable; there was hardly a year when she wasn’t quoted in newspaper food sections around the Fourth of July. But it was also becoming evident that Caesar would lose the battle for the country’s taste buds. The punch of anchovies that may or not be true to the first Caesar salad is the signature of today’s Caesar, which remains a staple of the American salad repertoire almost a century after its creation.

Or maybe neither of the recipes at the center of this familial food fight was on the menu in 1920s Tijuana. The oldest detailed recounting of that original salad I could uncover came from Caesar Cardini in 1952, some three decades after it was first served. He listed the ingredients that everyone can agree on: romaine lettuce, a one-minute egg, garlic croutons, hard, salty cheese, lemon juice, garlic, Worcestershire sauce and olive oil.

More divisively, he included the vinegar on the list—pear vinegar, to be exact—and left off the hotly disputed anchovies. He mentioned white pepper instead of black, an alternative that is mostly aesthetic, and probably forgot about the salt. And he threw in one ingredient that would have surprised Rosa and Alex and opens up a whole new Caesar salad controversy: mustard.

Caesar’s Caesar Salad

Created from Caesar Cardini’s memory of the ingredients in his first Caesar salad, the recollections of Rosa Cardini and Julia Child for proportions, and what Child called the “uniquely Caesar” technique. Start this recipe four days in advance of serving.

- Serves 4

Ingredients

- 2 cloves garlic

- 3/4 cup olive oil

- 2 medium heads romaine lettuce

- 2 slices good white bread

- 1 ounce Parmigiano Reggiano

- 1 lemon, juiced

- 1/4 teaspoon powdered mustard

- 1/2 teaspoon white pepper

- 1/2 teaspoon kosher salt

- 1 teaspoon pear vinegar

- 6 drops Lea & Perrins Worcestershire sauce

- 2 eggs

Instructions

-

Peel and crush the two cloves garlic and submerge in the olive oil. Cover and allow to steep for 4 days. Remove garlic before using oil.

-

In advance of preparing the salad, chill a large bowl and four dinner plates.

-

By hand, tear whole lettuce leaves from the heads. You only want the crispest portions of the leaves, so reserve outer leaves for another use if necessary. Wash and dry the leaves and wrap them in a tea towel. Refrigerate until ready to assemble salad.

-

Preheat oven to 250°F. Trim crust from bread and cut into 1/2-inch cubes. (You want about 1/2 cup of croutons.) Place on a baking sheet and bake until dry and lightly browned, about 25 minutes. After the first 10 minutes, drizzle with 1/4 cup garlic-infused olive oil. Stir cubes to coat and stir occasionally to prevent burning.

-

While croutons are baking, grate the cheese, juice the lemon, and place those items, along with the remaining 1/2 cup garlic-infused olive oil, spices, and other flavorings, in individual bowls, for assembling table-side.

-

When the croutons are ready, bring a small saucepan of water to a boil to make coddled eggs. Add the eggs and remove the pan from the heat. Let the eggs cook for 1 minute, and then remove them from the water.

-

To assemble, place the romaine leaves in large, chilled bowl. Pour half the garlic-infused olive oil over the leaves and give them two rolling tosses—using a fork in one hand and a spoon, scoop under the leaves at 3 o’clock and 6 o’clock and then move the utensils to 12 o’clock and roll them gently toward you.

-

Sprinkle with powdered mustard, salt, pepper, and remaining oil and execute the roll-toss once more. Add the lemon juice, pear vinegar, and Worcestershire sauce, and break the coddled eggs into the bowl. Roll-toss twice. Sprinkle with cheese, roll-toss again, and add the croutons. Roll-toss a seventh and final time.

- Arrange leaves, all facing in the same direction, on the chilled plates. Top with croutons. Serve immediately. Eat with your fingers.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook